Homage to the National Hero of Albania – written by H.E. Arian Spasse, Ambassador of Albania to Hungary

There were many episodes of historical contacts between Albanians and Hungarians. Some have been lost over time, others shine in collective memory or are brought to the surface by historians.

Acta Balcano-Hungarica 1., published by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in 2019, unveils some interesting Albanian and Hungarian characters, who have greatly contributed to the good relations between the two peoples. It is surprising to see how members of prominent Albanian families, elected to the highest ranks of the Habsburg Empire, or Ottoman Empire, left their mark on Hungarian soil. As Balázs Sudár points out, several members of the Araniti family “gained a foothold in the newly annexed territories of the former Kingdom of Hungary… The prestige of the family they had lost in Albania, was regained in Ottoman Hungary”. According to Zoltán Péter Bagi, “At the turn of the 17th century, Gjergj Bashta was one of the best soldiers in the Hungarian and Transylvanian theatres in the Long Turkish War against the Ottoman Empire”. Men of God, like Pjetër Mazreku, or Thoma Raspasani contributed to the preservation of Christianity in Hungarian Territories during the 17th and 18th centuries. Lajos Thallóczy, a Turanist historian, “…set the geographical boundaries for Albanian History” in 1898 with The History of Albania Written by a Gheg Who Loves His Country (Krisztián Csaplár-Degovics). In modern times, many know the White Rose of Hungary, Countess Geraldine Apponyi, who became the Queen of Albania.

Relations between Albania and Hungary were nurtured by many other characters, especially after 1900, who played a decisive role in important moments in history. However, the contacts between Skanderbeg and János Hunyadi rise above the others and bear strong symbolism. Not just because they were the most prominent figures of warfare who opposed the expansion of the Ottomans in Europe in the 15th century. As Arthur Goldschmidt Jr. wrote in A Concise History of the Middle East, “Having resumed the sultanate, he (Mehmed) led expeditions against two legendary Christian warriors, Hunyadi of Transylvania and Skanderbeg of Albania”. Over the centuries, they have earned the recognition of their people as freedom fighters, champions of liberty, defenders of Christianity. With their resistance against the Ottomans, they became mythical to their people.

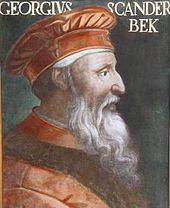

George Castriota (Gjergj Kastrioti), known as Skanderbeg (1405-1468), is considered a national hero in Albania, a symbol of Albanian identity and statehood, as well as of the Albanian resistance. His contribution was recognised and cherished throughout Christian Europe, which considered the Ottoman Empire to be the most dreadful foe at the time. Scanderbeg’s reputation was such that on 23rd December 1457, Pope Calixtus III declared him Captain-General of the Curia (Holy See) in the war against the Ottomans and gave him the title Athleta Christi, i.e. Champion of Christ. It was time when in Europe a new 500-mile war front came into being along the borders of Hungary, Bosnia, Serbia and Albania. Today we can say that the confrontation along this war front had a civilisation and religious background, and the clash was perceived as a religious war between the Cross and the Crescent.

Skanderbeg died on the 17th January 1468, after leading the Albanian resistance against the expansion of the Ottoman Empire for 25 years. He was able to unite Albanian nobles under his leadership, proclaim his war policy and successfully oppose Ottoman armies in both battle and diplomacy. After the League of Lezha (1444), he emerged as the military and political leader of the Albanians. As Marquis De Chambray wrote in his Philosophy of War, “Skanderbeg was not just a general, he was a political leader. You can impose a general to an army, but you can not impose a leader to a party. That’s why the death of a leader causes, almost always, the ruin of that party”. Was this the reason why Albania couldn’t resist the invasion? I can agree with De Chambray’s idea, but that’s not the case.

Since the inception of his war policy, Scanderbeg became vital to link Albania’s interest with the rest of Europe. Therefore, he sought allies among Western Christian powers such as the Holy See, the Kingdom of Naples, the Duchy of Milan, the Kingdom of Hungary, sometimes the Republic of Venice, the Duchy of Burgundy, Ragusa, etc. Relations with these allies were complex, as complex were their relations with the Ottoman Empire and complex was that Medieval period. Western Europe was on a transitional trajectory, Rinascimento, when Christian identity began to weaken, and the concept of statehood was not matching anymore with the concept proclaimed by the Pope that faith is a self-supporting argument worth of sacrificing state and personal interests.

So, the mid-15th century marked a turning point in European history regarding the anti-Ottoman wars. At the epicentre of this turning point was a major personality like János Hunyadi and then Scanderbeg, an equally great figure, who remained the last European military commander resisting and fighting to the death to protect his and his fellow countrymen possessions in Albania from the Ottomans, moreover hoping to throw them out of Europe.

Nearly 500 years later, at the end of 19th century and early 20th century, the Ottoman Empire disintegrated. While fighting to survive this process and come out as a nation with its own territory, the predecessors of the Albanian State were looking for modern and historical allies in Western Europe. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was one of the Western powers that supported Albania’s independence and the creation of the Albanian state in the Western Balkans. In 1896, the Ballhausplatz envisaged a new policy concerning Albania after the joint minister of Finance, the Hungarian Benjámin Kállay, drew attention to a threatening pan-Slavic iron ring (controlled by Russia) surrounding Austria-Hungary. During the First Balkan War, in 1912, Serbia’s attempts to reach the Adriatic coast prompted the Austrian and Hungarian governments to engage seriously. On the 28th November 1912 Albania proclaimed its independence.

Against this historical background, Skanderbeg’s relations with General and Governor János Hunyadi (1408-1456), and later with his son, Mátyás Hunyadi (King of Hungary 1464-1490) proved to be very important. Not so much for the results they have achieved, but for their efforts in establishing an alliance in the fight against the Ottomans. “These were hard times for Skanderbeg, but he had an ally, the Hungarian Hunyadi”, wrote Fan Noli, an Albanian priest and scholar in 1921, who dedicated many years to the life and achievements of Scanderbeg. These contacts were emphasised by historians and politicians over the years and have rightly gained symbolic status in the relations between Albania and Hungary today. Everyone in Albania knows about this alliance as it appears in all history books.

With a gesture of friendship, a few months ago, in 2020, the Municipality of Tirana donated a bust of Skanderbeg to the Municipality of Budapest. This masterpiece was made in 1939 by one of the best Albanian sculptors, Odhise Paskali (1903-1985). It will be placed in City Park, a few metres from the equestrian statue of János Hunyadi.

Unfortunately, due to the pandemic, the inauguration ceremony was postponed to a more appropriate moment.

If they couldn’t join forces on the battlefield, we will bring them together in Budapest.

H.E. Arian Spasse, Ambassador of Albania to Hungary

Source: Diplomatic Magazine