Written by: Mrs Krisztina Mosdóczy Source: Diplomatic Magazine

In 2020 we commemorated the 1956 Hungarian Revolution with a little-known and researched aspect of this historic event: about Hungarian children, who fled to Austria in an extremely difficult situation, for whom the Austrian government and the population manifested deep sympathy and humanity, providing significant humanitarian assistance to continue their lives.

The most famous event of the 20th century Hungarian history in the world is the 1956 revolution. Its defeat induced the largest wave of refugees in Europe after WWII. From October 1956 to April 1957 more than 200.000 Hungarians left their homeland, most of them fleeing to Austria. Thus, Austria, which had regained its freedom only a year earlier, was facing a great challenge. In November 1956, 113.810 people crossed the Hungarian-Austrian border illegally. Entering the land of Austria, they were granted political refugee rights. Austria, the gateway to the free world, was an intermediate station for some, but a new home for many people.

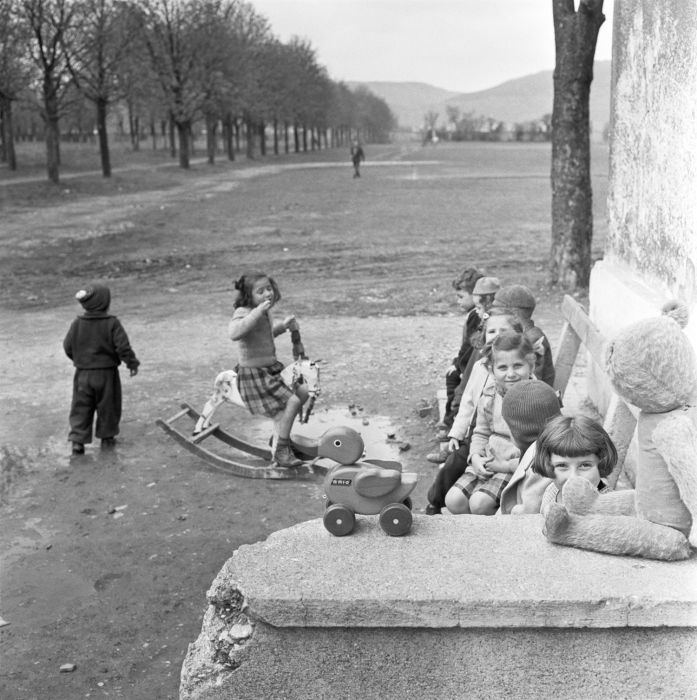

Numerous historians, political scientists and social researchers have already analysed the events of that time. The images of Hungarian refugees and families approaching the bridge at Andau live in our memory. Yet, have we ever thought about how many minor children and teenagers were forced to leave Hungary (even without their parents) and where their fate led them?

In Austria, help manifested in various forms: several public and private initiatives have been set up specifically to support children and adolescents coming from Hungary. If we take a look at the respective numbers, we understand the importance of this issue.

According to a survey conducted in February 1957, 60% of refugees were younger than 30 and more than 6% were under the age of 14. In his report of May 1957, Dr. Willibald Liehr, Head of the Hungarian Asylum Department of the Austrian Ministry of Interior registered 3665 youth between the ages of 14 and 18. Statistics as of 28th October referred to less, notably 1438 young people. By this time, tens of thousands of Hungarians had already left Austria for other Western European countries or overseas.

In March 1957, children under the age of 14 were also registered: the total number of Hungarian students was 3044, 861 in grammar schools, while 2183 in elementary schools.

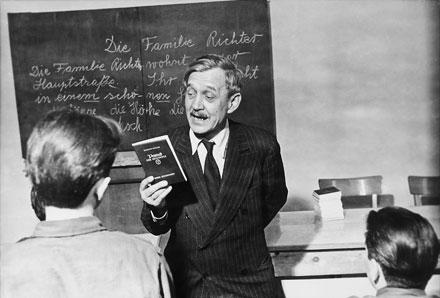

From the outset, the Austrian state provided children of compulsory school-age with the possibility of education. Initially, educational groups were formed inside the refugee camps, later separate Hungarian classes and even Hungarian schools were established. In December 1956, the Austrian Ministry of Education defined the tasks related to the education of Hungarian child refugees. Beside the acquisition of German language, the preservation of Hungarian language and culture was also the mission of elementary and grammar schools. Priority was given to the relocation of single children and teenagers from the camps to foster homes.

There were also personal initiatives for the care and education of juveniles. This is how the regional voluntary associations were founded, for example in Traiskirchen or in Stockerau (Lower Austria). Students belonging to these associations took their exams in Austrian elementary schools, many with the help of an interpreter. After completing elementary school, Hungarian youngsters could either study a profession or go to secondary school.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees convened a meeting in Vienna on 22nd January 1957 to discuss the situation and training opportunities of Hungarian secondary schools, as the main agenda item. At that time, approximately 1000 secondary school-age Hungarian children were living in Austria, whose fate was also decided at the meeting. In May, even a whole conference was held in Vienna to help young Hungarian refugees.

Five grammar schools were in operation in Austria: the Hungarian Secondary School Specialised in Science in Innsbruck, a secondary school in hotel Wiesenhof in Gnadenwald (Tyrol), one in Grän (Tyrol), the Hungarian Secondary School Specialised in Science in Kammer am Attersee, and the secondary school in Obertraun (Upper Austria) which later moved to Iselsberg. These schools started as private schools under the Provisional Schools Act of June 27, 1950, and were maintained by associations. Norwegian, French and Dutch charity organisations also played a major role in their funding. They clustered into a coordinating body called “Innrain 37” based in Innsbruck. In some schools, they wished to reach a higher number of students, thus rationalising operations. Despite the agreement and the initial serious financial difficulties, yet the above five schools were established, enabling a total of 746 Hungarian students to have access to education.

Extant data from documents of these schools reveal a high proportion of unaccompanied child refugees: e.g. 92,1% in Grän, 93,7% in Wiesenhof. Altogether more than 580 children arrived without parents.

Foster homes of Caritas Vienna (e.g. St. Ägyd am Neuwald, Unterdallach am Wörthersee) also accommodated 185 Hungarian students at that time. And 35 students attended other Austrian secondary schools under the supervision of the “Save the Child Society”. Thus, the total number of secondary school students reached 966.

By 1963, more than 800 students had successfully graduated from the five Hungarian secondary schools. In that year, the Secondary School Specialised in Science in Innsbruck was the last to be closed. The other Hungarians schools closed after two academic years in general, as no more child refugees arrived. These schools were exceptional, not only did they prepare the children for graduation, but also played an essential integrating role in making Austria the new homeland for many Hungarian children and young people. Interestingly, these schools – respecting the intention of Austrian and international authorities – were geographically far from Austria’s eastern border, and they were important bases of the later Hungarian organisations, associations, many of which are still active today (e.g. Scouts of Innsbruck).

Separate foster homes have also been set up for apprentices among others in Retz, in Spittal an der Drau, in Innsbruck and in Rum. The most famous was in Hirtenberg (Styria), where carpenters, locksmiths, car mechanics and electricians were trained in Hungarian. Boarding schools for trainees also operated in Greifenstein and Grießhübl (Lower Austria). Transitions were handled flexibly: should secondary school students change their minds, they could go to vocational training, and even many secondary school graduates decided to learn a profession.

We also need to mention university students, who had to interrupt their studies in higher education to flee Hungary. They could benefit from various scholarships (Rockefeller scholarships, Coordinating Committee – International Relief for Hungarian Students, etc.) and turned often to the Embassy of Hungary in Vienna to receive certificates about their previous studies from the Hungarian Ministry of Education. Thus, many could continue their studies at foreign universities or colleges.

Though in 1957 Hungarian students had not yet been able to take the Austrian final exams, but in March Dr. Heinrich Drimmel, Austrian Minister of Education, already confirmed in his letter addressed to the rectors of academic colleges that secondary school students could enrol in any Austrian college as “their qualification level meets the standards required from Austrian students”.

The Austrian education system responded very quickly and flexibly at all levels to the mass arrival of Hungarian children and young adults, thus providing them the possibility of studying from the very beginning, even in Hungarian.

An exhibition entitled “Hungarian Secondary Schools in Austria” opened in Vienna in November 1997, and in Budapest in 1998, presenting the secondary schools and this chapter of Austrian education history with a rich visual material and archival documents. The exhibition revealed a new facet of 1956 to visitors. Not only did these schools educate Hungarian children and trained them for life, but they tried to compensate for the lost homeland, to provide protection, a home, and at the same time to help them find their way in the new homeland.