Written by Mr. Carlos Eduardo Correa, Minister of Environment and Sustainable Development of Colombia

Chiribiquete National Natural Park has been listed as one of the biggest and best-kept secrets in Colombia. It is also known as the largest natural park in Colombia and one of the ten largest in the world. It was discovered in 1987, when the then director of the National Natural Parks of Colombia, Carlos Castaño Uribe unexpectedly came across this majestic and exceptional area while flying over the region. It did not appear on the country’s official maps.

In 1989, Chiribiquete was declared a National Natural Park by the Colombian state. It meant joining the Amazonian indigenous communities, who have been living in that place for centuries, in voluntary isolation to effectively protect this landscape. It is relevant to highlight that the guarantees to these indigenous peoples are also recognized by the Colombian State in Decree 1232 of 2018, which includes the right of these communities to live freely in accordance with their culture and not to be contacted.

Chiribiquete is considered a unique place in the world for its privileged location at the confluence of four biogeographical provinces: Andes, Amazonas, Guyana, and Orinoco. It is a key area for the conservation of threatened species, such as the jaguar, pink dolphin, tapir, macaw, and giant otter. Therefore, it conserves an extraordinary biological richness that is evidenced in the 1801 species of vascular plants, 42 of which are endemic, 209 species of butterflies, 60 species of reptiles, 57 species of amphibians, 492 species of birds, 82 species of mammals and 238 species of fish.

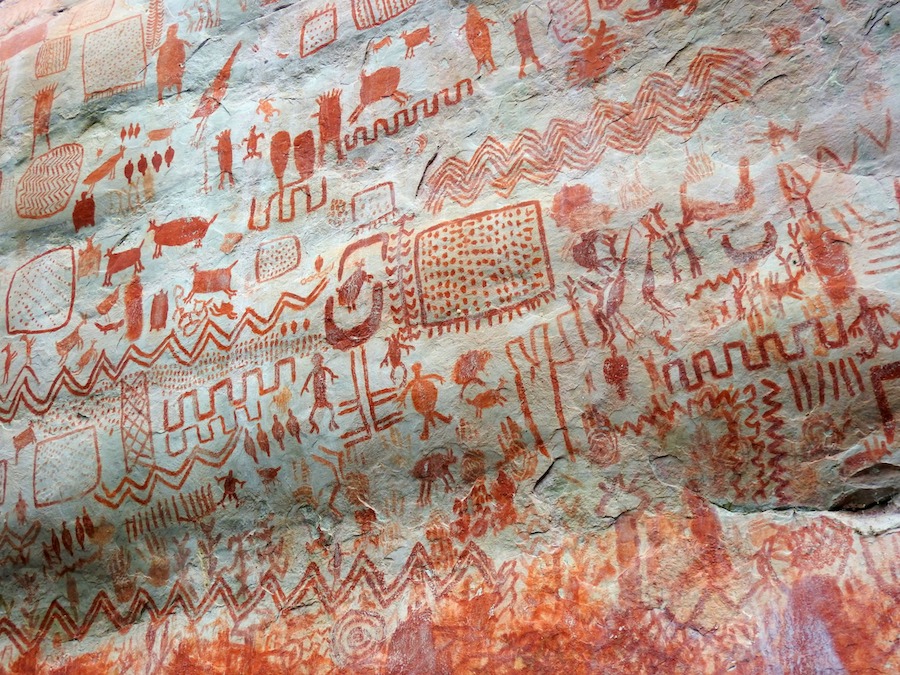

Its historical and cultural importance is represented in the great archaeological fields, in which more than 50 pictorial sites (cave art sites) are observed with no less than 70,000 drawings from around 22,000 years ago.

One of the most surprising and outstanding features of cave art has to do with the fact that the artistic ensembles show a continuous sequence of manifestations of pictorial use, perhaps from the end of the Pleistocene to the present day. Indeed, there is evidence that recent paintings are probably made by uncontacted indigenous groups or in voluntary isolation.

The Rupestrian art in Chiribiquete related to paintings of flora, fauna, hunting and other practices of different ethnic groups, contributes to the understanding of indigenous communities that have inhabited this part of the world for thousands of years. These paintings contain important secrets of the history, thought system and worldview of the indigenous communities of the Amazon. In addition, the dates of these paintings generate important debates when it comes to conceptualizing the occupation of the American continent.

One of the most outstanding features of Chiribiquete are the Tepuis, table-top mountains in the Guyanese Shield, which have special rocky shelters almost as if they had been made to prevent water and wind from damaging the murals over time.

According to Carlos Castaño Uribe’s research, there are clear indications of complex mural selection processes, as well as advanced techniques to make them so difficult to access in places that helicopters and specialized climbing equipment are required, and sometimes even that is not enough.

One can ask, how the indigenous people managed to paint these murals in these inaccessible places with little more than the plants that surround them? The only possible explanation is their high level of social and spiritual development.

The good condition of this area allows strategic ecosystems to maintain the flows of matter and energy on which the integrity of the park depends. The Chiribiquete ecological characteristics contribute to the regulation of the global climate and maintain the regional water balance.

For this reason, the 42nd Session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, held in July 2018, declared it a Mixed World Heritage Site. With this inclusion in the World Heritage List, UNESCO clearly calls for the protection of this place. The area declared a world heritage site was 2,782,535 hectares, a size similar to a country like Belgium. This area was expanded by the National Government of Colombia in June 2018 to 4,268,095 hectares, equivalent to the size of a country like Denmark.

This landscape is so unique that its loss would be a regrettable event not only for Colombia, but for humanity. That is why the Colombian state and its citizens have a global commitment to conserve Chiribiquete: the Cosmic Maloca of the Jaguar.

Today, taking into consideration the challenges we as humanity face in tackling climate change impacts, deforestation, and the loss of biodiversity, from which Chiribiquete is not exempt, I recall the invitation made by Colombia before UNESCO to States, Multilateral Organizations, NGOs and communities to jointly protect this unique place with an invaluable biological, historical and cultural richness.

Source: Diplomatic Magazine