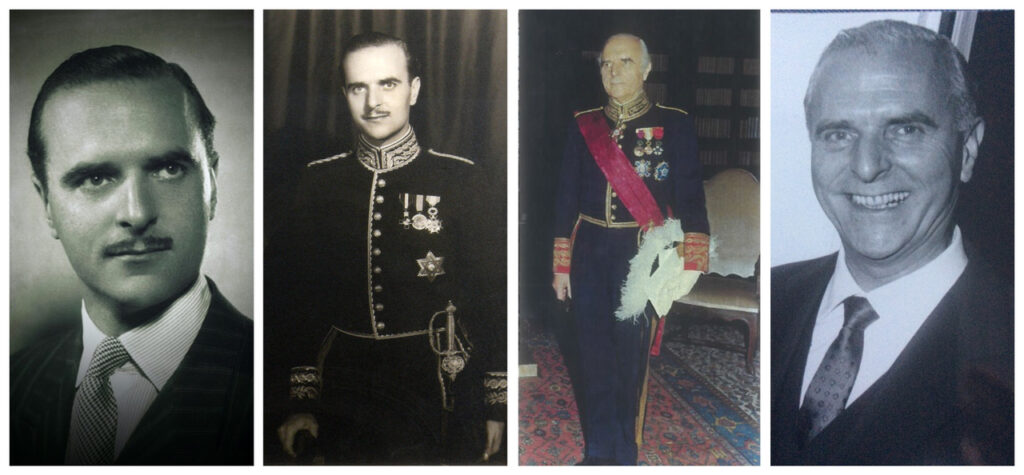

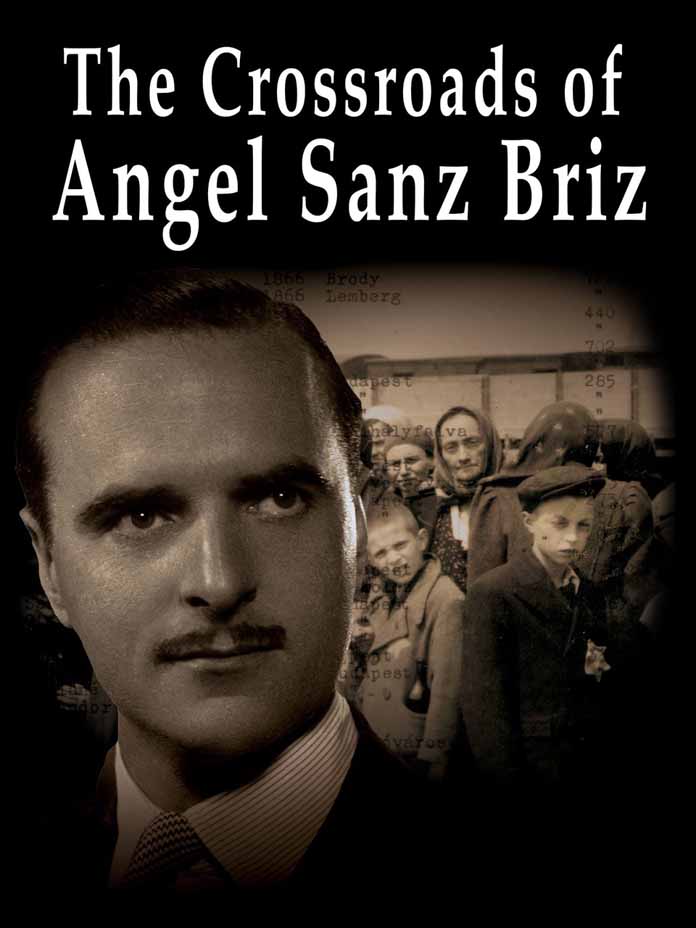

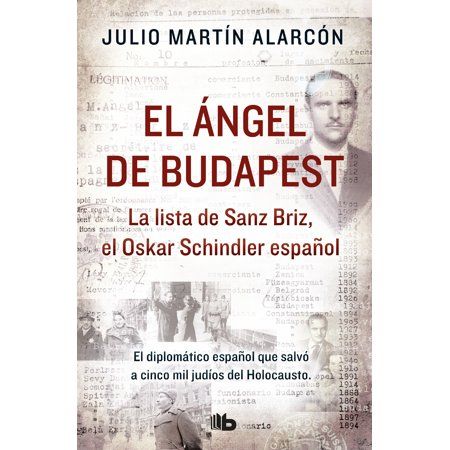

Interview with Juan Carlos Sanz Briz and Angela Sanz Briz

by Anna Popper, Senior Editor of the Diplomatic Magazine

What is the family background of Ángel Sanz Briz and how did he become a diplomat?

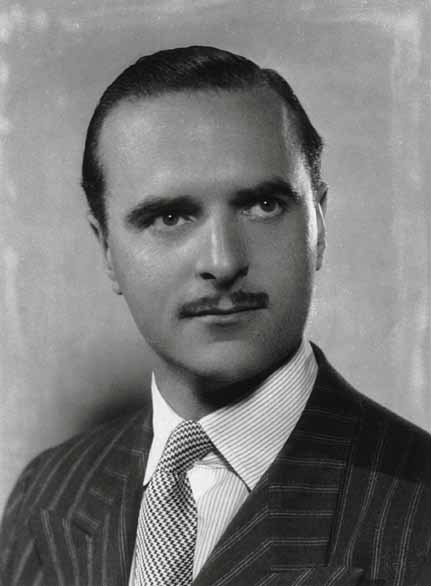

– Ángel Sanz Briz was a diplomat. He wanted this from a very young age. Born in Zaragoza, in a family of merchants with four brothers and one sister. After finishing his studies of law, he entered the Diplomatic School in Madrid. He started his diplomatic career just before Franco became chief of state and the Spanish Civil War broke out. Our father was the first in the family to choose diplomacy as a career.

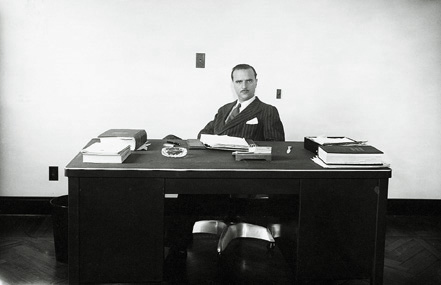

Tell us please about your father’s humanitarian activity in Budapest, serving as First Secretary, then Chargé d’Affaires of the Spanish Legation, at the age of 34.

– After the first diplomatic posting in Cairo, our father was sent to Budapest in 1942. It was a tough time for him as he was a junior diplomat with no experience in dealing with difficult situations. He was recently married and had a baby daughter, born in Budapest. So, acting without the permission of his government was something that could endanger his own life and risk his diplomatic career. Obviously, it was very challenging, because he had very few means to help the Jews, saving them from deportation to concentration camps.

He had a small team to deal with the situation and provide shelter for thousands of refugees in his own house, the legation premises and the 11 houses he rented in Budapest, thus creating a Spanish safehouse-system. It was indeed a difficult and dangerous action. We believe our father used his own money to rent houses, and perhaps some people of the Jewish community also helped in the expenses. He did all he could to save as many people as possible.

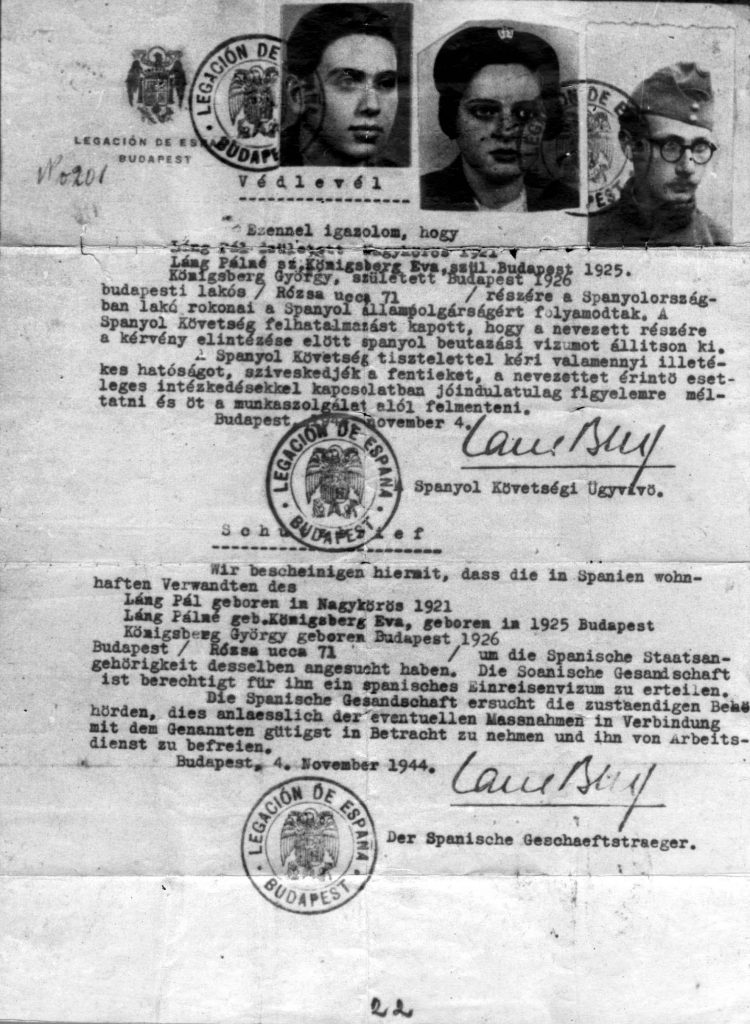

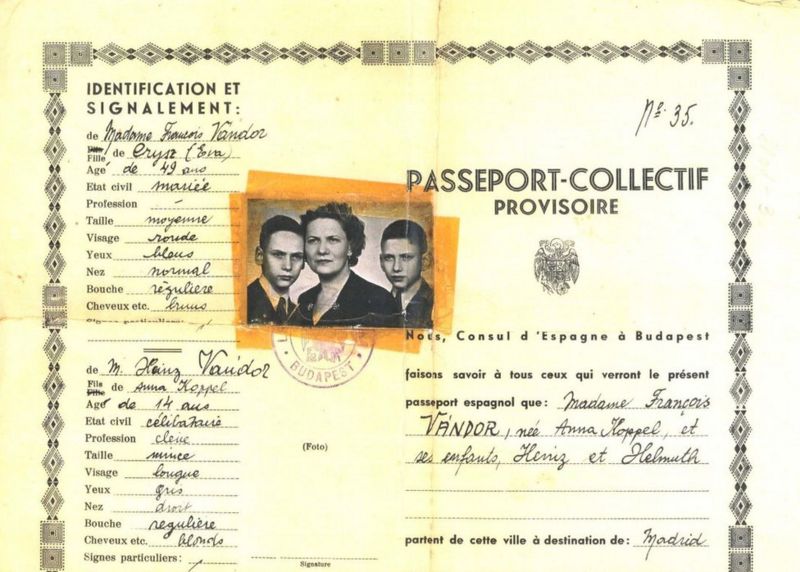

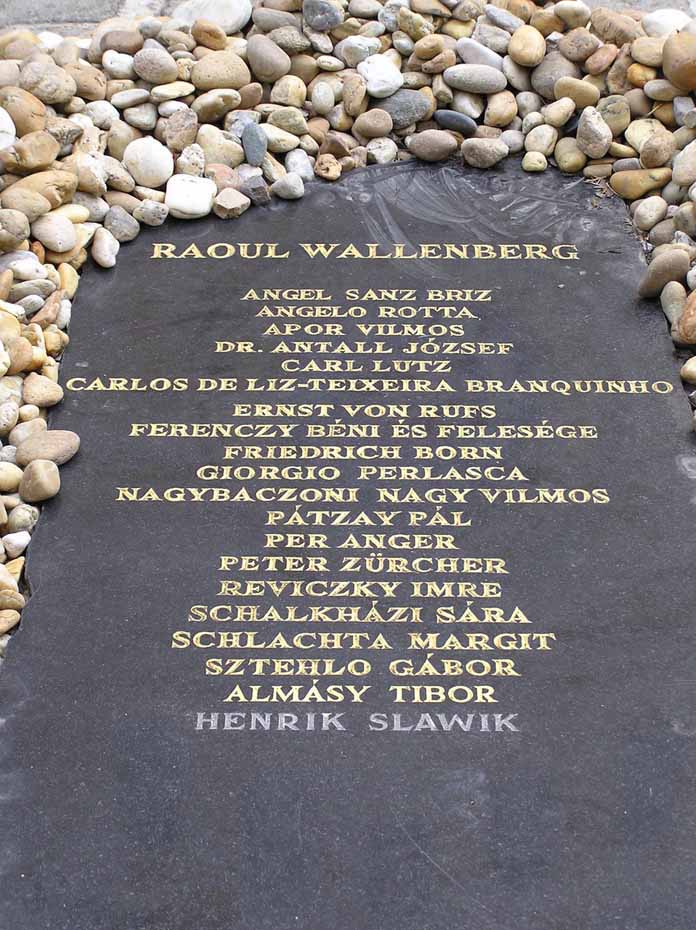

Our father first obtained permission from a high-ranking Hungarian official to issue up to 200 passports for Hungarian Jews, but only of Sephardic origin. He convinced the Hungarian authorities that Spain had given Spanish citizenship to descendants of Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain in 1492. Such a decree was issued in 1924, but was repealed in 1930, of which the Hungarian authorities were unaware.

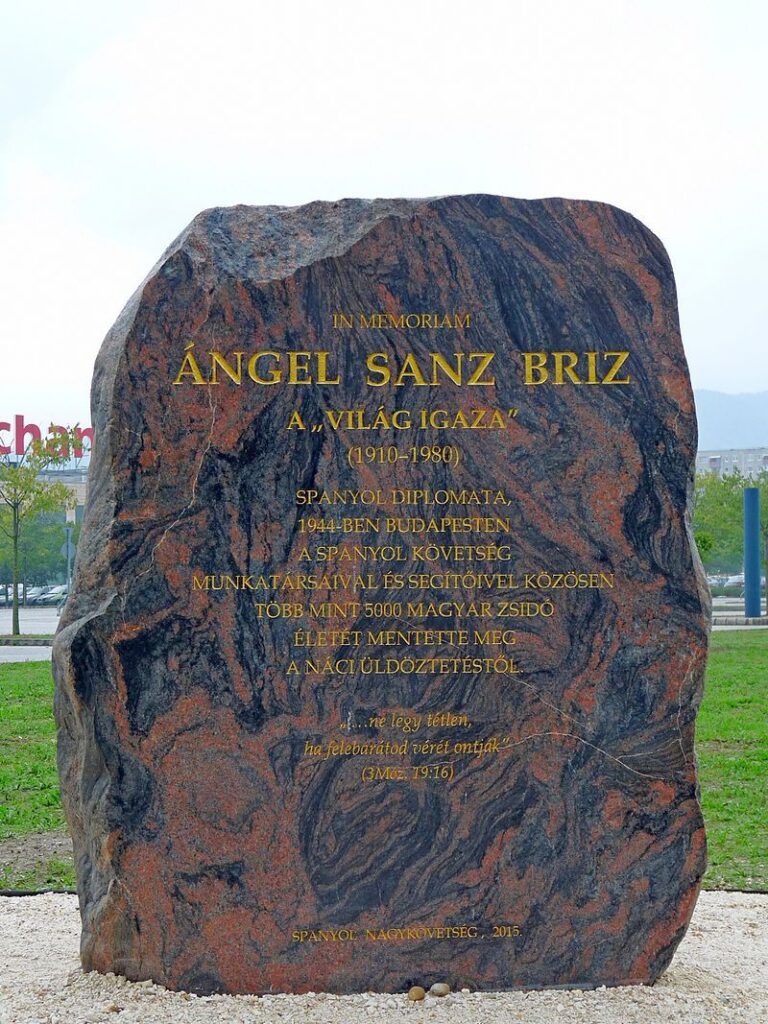

But there were very few Sephardic Jews in Budapest, so our father started protecting Ashkenazi Jews, too. With the permission to issue 200 passports, he produced about 2500 documents – like letters of protection – officially numbered, but never using higher numbers than 200. (They were like 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, etc.) And instead of personal documents, he provided family documents, thus saving a whole family with one document. The number of saved Jews reached about 5200.

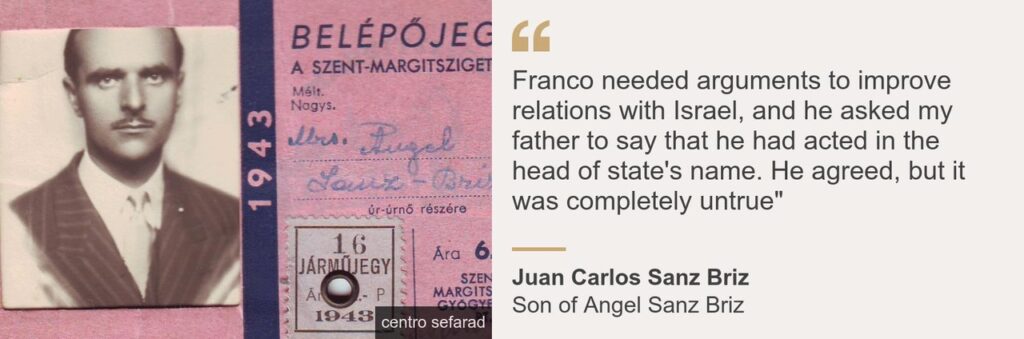

He acted on behalf of Spain without the permission of Spain. When the Spanish Foreign Ministry learned of his actions, the war had ended, and so there was no negative reaction. In December 1944, as the Red Army approached Budapest, he followed government orders to leave for Switzerland.

Did you have the chance to meet people your father saved?

– We have met some of the Jews our father rescued. It’s been such an emotional situation, so wonderful to hear their stories and remembrance. We visited Budapest on several occasions, and always met people, saved by our father. We have seen many protection letters signed by our father and family photos, brought by those people. In 2019, I was in Budapest for the European Maccabi Games, I carried the Spanish team flag with Eva Benatar born in Budapest, she was 9-month-old baby when my father saved her.

Sanz Briz had a very successful diplomatic career after Budapest. Can you tell us about his professional life?

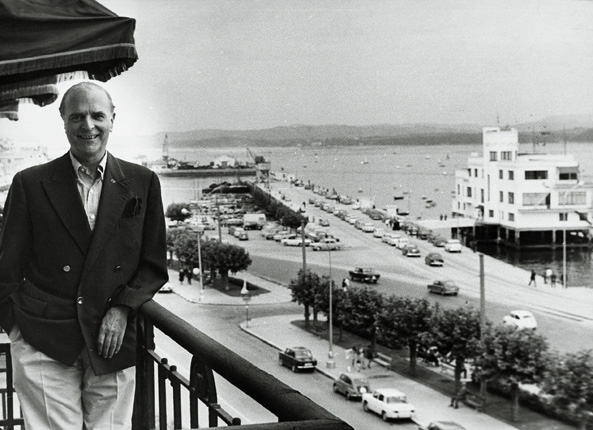

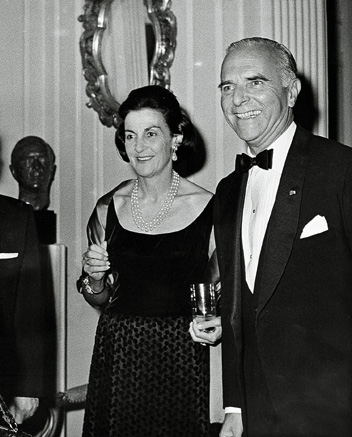

– Our father had a great diplomatic carrier with exciting assignments, representing Spain seven times as ambassador. I think, the most interesting posting was to China in 1973, as the very first Spanish ambassador to open relationship with the country. Then he was sent to Rome as Ambassador of Spain to the Holy See. This mission was important, because at that time the Concordato – the treaty between the Holy See and Spain was being negotiated. He had the honour of serving as ambassador under three popes – Paul VI, John Paul I, and St John Paul II, until he died on 11th June 1980 in Rome.

Did your family know about the details of his moral courage and the very important humanitarian actions he undertook voluntarily while he was posted to Hungary?

– Our father seldom talked about his humanitarian activities in Budapest, unless you asked him, then of course he told about this work of which he was very proud, but never bragged. We, his four children, knew the story, but without the details of horror. He was so happy he could help. He always said it was the most important thing in his life he had ever done. We children thought it was more or less normal. The older you get, the more you know and realise how difficult, how dangerous and how important it was. Our father never thought he should receive any gratitude or public recognition in return. He had done what he had to. Because of his feelings, way of thinking, humanitarian morals, he just did it as his duty. And it was such an extremely horrible situation that he didn’t really like to talk about that much.

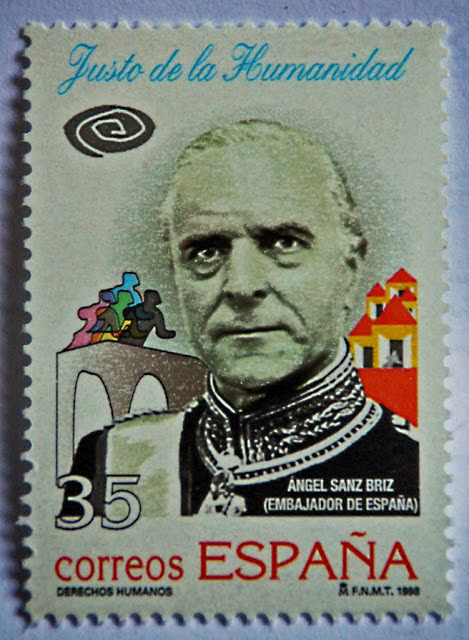

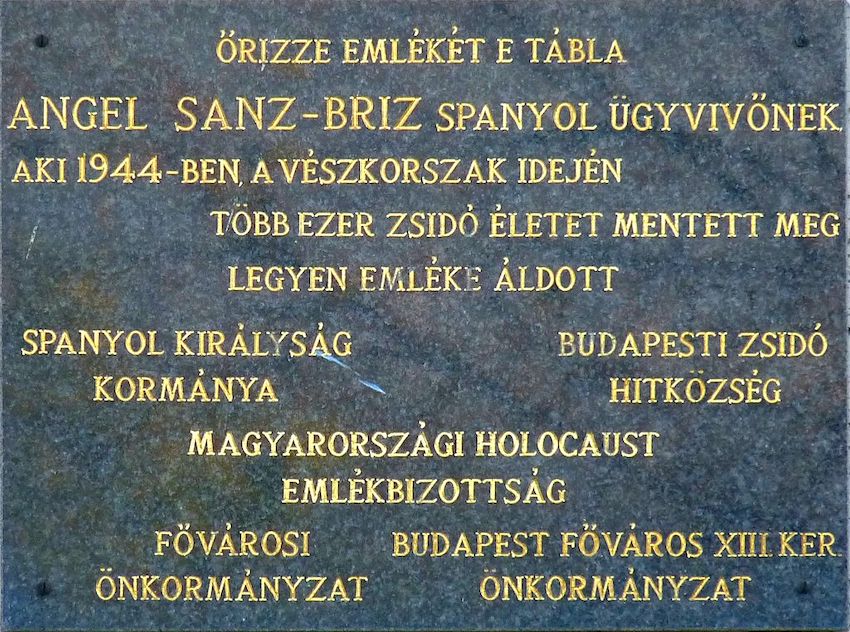

The “Righteous Among the Nations” award was bestowed to him for his life-saving deeds. How did it happen that he could not accept it?

– In 1966, the State of Israel contacted our father to tell that he was named “Righteous Among the Nations”, and he will receive the award in Israel. Asking permission from his government, he got the answer: it’s better not to go, because our foreign policy depends on the Arab countries. So, our father thanked Israel for the honour, saying he could not accept the award.

The Yad Vashem Holocaust Centre was extremely nice, and after Spain and Israel established diplomatic relations, in 1991 my mother – on his behalf – received the award of “Righteous Among the Nations”. What is important is that he understood that the State of Israel recognised him as a hero, who acted very generously, risking his life while saving innocent Jews. Our father believed he had acted as any human being should do in those circumstances without deserving any recognition.

How do you remember him as a father?

– He was a fantastic father: amusing, friendly, funny. As a diplomatic family we travelled together, living in different countries. He was strict with us in studies and behaving, but he was a kind and loving father. We have great memories with him. He told us about his life and it was awesome to hear them. He was always reading, it was his passion. I think his other hobby was working. He loved his job. We supported him and the whole family was proud of him. We have a large family of 47, being very close to each other.

What did you learn from your father?

– The most important thing we learnt from him is: when you have to do something and you can, do it. Don’t look the other way. If you like it or not, dangerous or not, easy or not, you have to do it. My father did it for lots of people. Another important lesson: you have to be responsible for your life and work. And be a good person. These three things our father drilled into us. His humanitarian sensitivity came from education, from a family with good principles. Interesting fact that there were no Jews in Spain, so our father really acted on a humanitarian basis. It was not political, not religious, not economic motivation. It came from his heart and morals.

What would be your message on the double anniversary?

– First, we convey our thanks for writing about our father. Our message: it is important to remember the Holocaust and those who saved innocent lives, because we hope that by talking about them, others will be inspired to do the same. Such great people should be an example to others. One of them is our father.