A stunning Renaissance sculpture has been identified in the collection of the Spiš Museum in Levoča, Slovakia, according to The Slovak Spectator, which first reported the extraordinary news. The life-size Carrara marble bust depicting Cecilia Gonzaga, a noblewoman from the influential House of Gonzaga in Mantua (Mantova), Lombardy, Italy, is now believed to be the work of the 15th-century Italian Renaissance master Donatello. If confirmed, this would mark only the eighth known sculpture attributed to the Florentine genius, making it an extraordinary revelation with far-reaching implications for the art world.

The Astonishing Story of the Sculpture

Portrait busts were rare in Donatello’s era, adding to the significance of this discovery. Commissioned in the 15th century by the powerful family of Gianfrancesco I Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua, this remarkable bust was likely created during Donatello’s time in the city. It is believed to represent Cecilia Gonzaga (1426–1451), a young noblewoman of exceptional intelligence and an extraordinary life story. Defying her father’s wishes, she refused an arranged marriage and chose instead to continue her studies. This decision, however, met with strong opposition from her father. After her father’s death, her determination led her to seek refuge in the Convent of Santa Lucia in Mantua, founded by her mother, Paola Malatesta.

Experts suggest that the sculpture eventually arrived in former Upper Hungary through the Hungarian noble Csáky family, who had extensive landholdings in present-day Slovakia, particularly in the Spiš region. It is speculated that the piece was passed down through marriages or cultural connections with Italian aristocracy, with whom the Csáky family maintained close ties since the 17th century. However, the exact route remains unclear.

For centuries, the bust was kept at the Csáky family manor in Spišský Hrhov. After World War II, the estate underwent an unexpected turn of events when it was converted into a reformatory school for girls. In a surprising twist, the students treated the masterpiece like a mere toy – one eyewitness recalled children rolling it around like a ball and even drawing circles around its eyes with a pen.

A Fortunate Rescue

In 1975, the head of the local institution recognized the bust’s artistic value and arranged for its transfer to the Spiš Museum in Levoča. However, it was mistakenly catalogued as a 19th-century imitation and simply labelled as a “marble bust of a woman by an unknown artist”. Placed in storage, it remained overlooked for decades until art historian Mária Novotná, the museum’s former director made a ground-breaking observation. She noticed an inscription on its pedestal: “CECILIAE GONZAGAE OPUS DONATELLI”. Since Donatello rarely signed his works, this inscription could be key evidence of its authenticity.

Novotná initiated further investigations and sent the sculpture to the Slovak Academy of Sciences (SAS) in Bratislava for examination.

A Scientific Breakthrough

After extensive research and authentication by art historian Ph.D. Marta Herucová at the Slovak Academy of Sciences, it is now highly likely that the bust is the work of Donatello.

In 2021, Marta Herucová published an extensive article on her study of the bust in French, which appeared in Revue de l’Art (CAIRN-INFO, 2021/3, No. 213). The article, titled Un buste de Cécile de Gonzague: Donatello, contains numerous photographic illustrations.

Researchers have since presented compelling evidence attributing the bust to the renowned Renaissance master. Initial analyses highlight stylistic elements – such as the intricate hairstyle, lifelike facial expression, and delicate rendering of fabric – that closely align with Donatello’s known works. Moreover, the fact that the bust portrays a historical figure is particularly noteworthy, as Donatello rarely created portraits of his contemporaries.

A significant comparison has been drawn between the signature on the Levoča bust and those on other verified Donatello sculptures, including Judith and Holofernes (1457–1464) at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence.

Further research in Florence included comparisons with the tomb of Antipope John XXIII, strengthening the case for attribution of Donatello’s authorship.

Adding another layer to the bust’s provenance, Marta Herucová contacted Austrian art historian Moritz Csáky, whose family once owned the castle in Slovakia. Count Csáky confirmed that he remembered the bust from his childhood.

If authenticated, this discovery will represent a remarkable new addition to Donatello’s oeuvre and elevate the Spiš Museum’s status on the global cultural map.

Exhibition Plan

Despite the groundbreaking discovery, this remarkable artwork is not yet on public display. It can currently be admired through digital 3D visualization: https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/ceciliae-gonzagae-sm-7156-9dac3be34f894e94815b7c691e8971f5

According to the new director of the SNM-Spiš Museum in Levoča, Mr. Ján Pavlov, who assumed office on 1 March 2025, the museum plans to present this previously unexhibited Donatello masterpiece to the public later this year. The occasion marks exactly 50 years since the artwork was acquired for the Spiš Museum’s collection in Levoča.

Levoča, a beautiful small town in eastern Slovakia, was founded in the 13th century and is renowned for its well-preserved medieval architecture.

The town, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is now at the centre of an art-historical sensation.

If confirmed as an authentic Donatello, this bust will not only enrich the museum’s collection but also solidify Levoča’s place on the world stage of Renaissance art history.

The Significance of Donatello’s Works

Donatello (c. 1386–1466) was one of the most influential sculptors of the early Italian Renaissance, known for his pioneering use of perspective, realism, and classical inspiration. His most celebrated works include:

David (c. 1440s–1460s) – on display at the Bargello Museum in Florence, this was the first freestanding nude male sculpture of the Renaissance. Notable for its contrapposto stance and sensual naturalism, it remains one of Donatello’s most famous works.

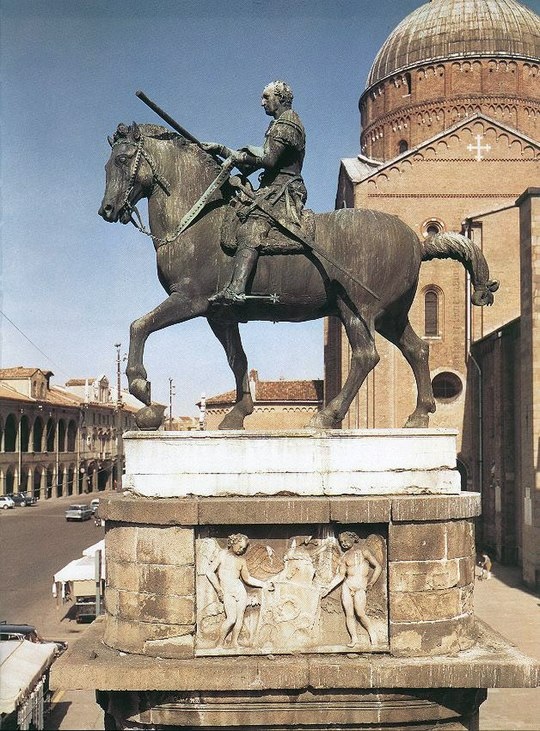

The Equestrian Statue of Gattamelata (c. 1445–1453) – located in Padua, this is the first life-size equestrian statue since antiquity, symbolizing power and influencing later Renaissance and Baroque equestrian sculptures.

Sources: Slovak Spectator, Spiš Museum in Levoča, Wikipedia

Photos from Facebook/SNM-Spišské múzeum v Levoči, Spiš Museum in Levoča

Pisanello’s 15th-century Cecilia Gonzaga Medal

A native of Pisa and renowned for working for the Doge of Venice, the Pope in the Vatican, and at the courts of Verona, Ferrara, Mantua, Milan and for the King of Naples, the celebrated Renaissance master Pisanello (Antonio Pisano 1395–1455) left a remarkable legacy, including an extensive collection of drawings and several paintings.

He is also credited with inventing the commemorative portrait medal, inspired by ancient Roman coins, which featured rulers’ portraits alongside allegorical imagery. These medals served both as tribute and as a treasured memento of individuals and significant events.

This unique bronze medal from 1447, titled “Innocence and Unicorn in Moonlit Landscape” – the first to depict a woman – portrays Cecilia Gonzaga, the highly educated and cultured daughter of Marquis Gianfrancesco Gonzaga. Choosing a life of devotion over marriage, Cecilia entered a convent shortly after her father’s death. Pisanello presents her in secular court attire, implying that he may have drawn inspiration from an earlier portrait.

The Latin inscription reads: CICILIA • VIRGO • FILIA • IOHANNIS • FRANCISCI • PRIMI • MARCHIONIS • MANTVE

Rich in symbolism, the reverse of the medal depicts a partially clad maiden – an embodiment of innocence and chastity – gently taming a unicorn. In medieval lore, this immortal creature could only be subdued by a woman of pure virtue. The unicorn serves as a dual symbol of Christ and wisdom, while the crescent moon, linked to Diana, the virgin goddess of antiquity, highlights the humanist revival of classical themes.

The medal is housed in the Robert Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Sources: Wikipedia, SNM-Spišské múzeum v Levoči, metmuseum.org

Images from the Facebook/SNM-Spišské múzeum v Levoči, metmuseum.org, italianrenaissancemedals.com