Interview with Ana Veydó, Singer and Bandleader of Cimarrón Group of Joropo music from Colombia

Edited by Anna Popper

Hungarian audience likes very much the Latin American music and they were so lucky to be able to attend Cimarrón’s live concert as a part of the two-day Festival of Distant Cultures on 16 July 2023 in Budapest. Have you ever been to Hungary?

– We have never been to Hungary, but I am a big fan of Hungarian music. I love Hungarian artists like Monika Lakatos. We have always wanted to perform in this country, so this was a dream that came true.

I had the chance to be present at your fantastic concert, congratulations! I was fascinated by the spectacular show of talented and dynamic young musicians with a super singer and your powerful joropo music. How did you like the concert that was held four days before celebrating the 213th anniversary of Colombian Independence?

– We were very excited and pleased to perform here in Budapest on the stage of the amazing Hungarian House of Music in the beautiful City Park. This majestic building with unique architecture, inaugurated last year, is entirely dedicated to music, mankind’s most international language. The technical conditions are just perfect, the staff was extremely kind and professional with us. We enjoyed the concert so much, the audience was really extraordinary, enthusiastic and perceptive, we were from the first moment on the same wave with the packed music hall. We are so much impressed by this first experience and hopefully we will come back.

Please introduce the Cimarrón band, its members and the instruments they play. What was the founder’s idea? When did you become a professional band?

– Cimarrón is the only band that has taken the music of the Orinoco to the world. We have performed in 42 countries, now including Hungary, since Carlos Cuco Rojas and I decided in 2000 to make Cimarrón a professional band. We’ve been touring the world for 23 years.

The members of Cimarrón are constantly changing. I choose young Orinoquía musicians who don’t have the opportunity to show their talent on the local scene and I invite them to join the band to tour the world.

Cimarrón is radically different from what the world is used to hear from Colombia, presenting our unique llanero harp and guitar-like cuatro and bandola, percussive stomp dance and deer-skull whistles.

The African heritage in joropo had always been denied in Colombia. The joropo’s most evident African heritage is in the foot stomping dance. In joropo recordings, the dance was lost. This made us think that we should include it in the sound of the joropo on stage and we decided to amplify it through the Afro-Peruvian cajón, also the tambora and the surdo. That’s why we have a powerful percussion sound, but we are not doing anything that isn’t in the traditional joropo. In tradition it exists, but it is expressed with the zapateos or foot stomping dance. Our llanero harp is played with nails, not fingers. We have believed that the llanera harp technique is more similar to that of the African kora than that of the classical harp.

The cuatro comes from the small guitars of the Colonizers. It is a melodic and rhythmic instrument, it marks the harmony in the joropo and has the function of accompaniment. The cuatro llanero is usually the base of joropo, but in the case of Cimarrón the cuatro is no longer the instrument that sets the rhythmic base, since the inclusion of the cajón has allowed us to free the cuatro so that it also becomes a melodic instrument. Everything is supported by percussion and bass, giving each instrumentalist, including the cuatro player, the necessary guidance to find scenic richness.

The llanera bandola is an instrument of the laud family. In the case of Cimarrón, the bandola is as important as the harp. For us it is the leading instrument of the melody and the vehicle to generate melodic dialogues with the harp, with designs that give equal relevance to both.

In the format considered traditional, maracas are the only visible percussion of the joropo. It was believed to be the indigenous contribution to the joropo. However, to view maracas as the sole indigenous contribution is a denial of essential indigenous contributions. In the melodies of the joropo, the indigenous melodies survive, especially in cow milking songs. Cimarrón also brings on stage the deer-skull whistles inherited from nomadic indigenous communities.

But we also added the Guitarro, a tiple that comes from the Andean tradition and was important in the development of Colombian joropo in the 20th century. We are pioneers in bringing it back into the llanero instrumentation and putting it to the scene, because it was gone.

Of course we brought the conception of the joropo back from the power of zapateo, but expressed in the percussions we have added to this music.

What are the main characteristics of joropo music, originating from your homeland, Colombia? What are your musical roots?

– First, Joropo was the name of a popular festive reunion that was banned by the authorities during Spanish Colonization. There is reference of Joropo in archives founded in the territory of present-day Venezuela, alluding to a social dance reunion. So joropo has its roots in the zapateo dance and everything we know today is part of the rhythmic cell of the zapateo.

If we wanted to talk about joropo as a musical genre, it could not be described as such until the 1950s, when the cohesion process of its acoustic, stylistic parameters had already matured.

In the specific case of Colombia, there are clear descriptions of musical rhythms similar to those known today as joropo, but with formats based on Colombian Andean instrumentation. The format that was imposed as joropo or llanero music was the one with a harp, cuatro, maracas and bass. Joropo was built on this format in both Colombia and Venezuela after the 1950s. In both countries it was unanimously accepted as “Llanero Music” and that is how it became the musical genre that identifies a region and specific people in the vast region of Los Llanos (Colombia and Venezuela).

Joropo has been the leading discursive practice of the male-centric cowboy tradition from the cattle ranches. So we are trying to be more inclusive and working hard to recognize the diversity of the region and all identities out of the norm of cowboy codes.

The Hungarian House of Music, host and venue of your concert in Budapest, promoted your music style as the main attraction of the Festival of Distant Cultures as “a genre that has an exceptional sound even within the Latin music sphere”.

– It is true that the joropo is a very little known music. Colombia presents binary rhythm music to the world. Our music is not easy for the public to dance to. Music such as cumbia has had greater diffusion in the world.

You are the frontwoman, leader and star of Cimarrón group and along with the entire ensemble you contributed largely to winning Songlines Award, of which you can be very proud! How did you become a singer?

– I was born in the countryside, west of Boyacá, Colombia, in the warmest zone of the Andes. My parents grew coffee and sugar cane, but also had cattle. The most vivid image I have is of my mother picking coffee with palm baskets woven by herself, while my sisters and I moved the calves aside. In the afternoon, when we finished work, the radio played llanera music, or Joropo. That’s how I met and learned to love this music.

Venezuelan radio stations reached Boyacá and deliver us a joropo sound in the form of harp, cuatro and maracas, but Colombian radio played similar tunes with tiples and Andean guitars. The Venezuelan format struck me more, especially songs that spoke of the rough work in the countryside, with such a fast and vigorous rhythm. Songs talked about everything I experienced back then, even though I hadn’t been born in the Llanos. Because of my character, I immediately felt identified with what I was hearing.

I insisted on getting much closer to the joropo that men did and I wanted to sing like them. I started competing in Joropo music festivals just at a time when the recio singing style category was opened to women. I was one of the pioneers of recio singing style in Colombia. Recio means male fast and high pitched singing.

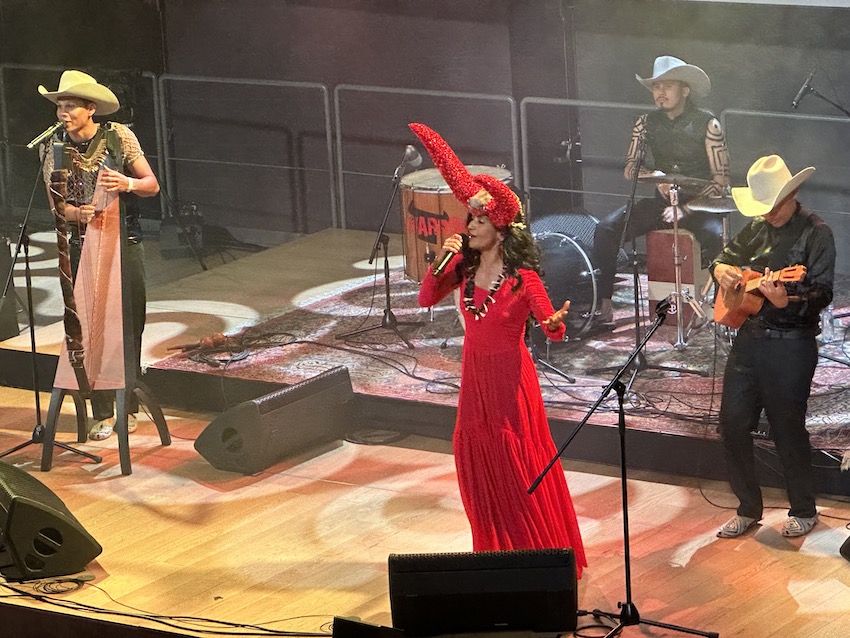

You and your band have a very impressive visual appearance on stage.

– We really like that people perceive the spirit of the Orinoquía. We want people to feel the power of this music, but also feel the joy of our cultural heritage. We want to show that very young musicians with their own ancestry can do wonderful things.

In 2020, the band lost its charismatic harpist and songwriter, Carlos Rojas, aka Cuco. What was the emotional and professional impact of losing your founder?

– Clearly, it had an emotional impact on me because Carlos was my partner in Cimarrón but also my partner in sentimental life. I think his death affected us a lot on our image as a band, because Carlos was always the central image of Cimarrón. After he passed away, my view of my own figure within Cimarrón changed and I had to prove publicly that not only was I the singer, but that I had always walked in the direction of the band through 22 years. In the first few months after his death, from the band and from outside there was a constant invocation of the figure of Carlos, sometimes with many doubts about the band’s possibilities to survive without the direction of a man. Now, there is no other option but to accept that the band will continue with me as leader. Carlos was my main interlocutor and his loss meant I was left without that person with whom I could reflect on Cimarrón. I will continue to be accompanied by the dreams we both had and Carlos will be my creative force. In fact, this new album is full of concepts we have worked on together over the years. The best way to remember him will be throughout what we do as Cimarrón.

In which parts of the world are you best known and where have you achieved the greatest success?

– We have a huge audience in the USA, because that’s where we recorded two of our albums for Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. We were also nominated for the Grammys in the USA. But in the UK they also love us a lot. We have toured more in the UK than in Colombia. There are people who have waited up to 12 years to see a Cimarrón concert in the UK again.

Regarding music recording, when did you released your last album?

– Our latest album is called La Recia and was released in May 2022. Many critics and journalists have praised this album in 14 countries. It was #1 on the Transglobal World Music Chart and blasted Top 10 of Best Folk Music Albums by Financial Times.

Was your concert in Budapest somehow different from the other performances? How much has the band changed since its foundation and in which respect?

– Each tour represents an opportunity for us to renew ourselves and update the band from their speech, according to the times we are living. There have been great changes over the years. But one of the most important changes has been embracing my leadership as a woman in Cimarrón in the last three years and that was reflected on the stage.

What are your future plans regarding touring in foreign countries? How do you see the challenges you have to face?

– We called this tour “La Gira Mundial del Joropo” (“The Ultimate Joropo World Tour”). We want this to be a two-year project. After this summer in eight countries, we will continue traveling in fall/autumn. We will go to the US and have plans to visit some Asian countries as part of the same tour in 2024.

The challenge will always be to represent music that is not widely known in the world and to be the pioneer band in Colombia to have an international joropo career. Nobody paved the way for us: we have made the path in the world for joropo, competing with much more effective music in direct connection with the public.

If you were granted a wish that would become true, what would you wish for?

– Continue positioning a genre like joropo at the level of world music.

And the next day you travel to the UK…

– We always dreamed of bringing our music to Hungary. And we knew that dream would come true, but we never imagined it would be this way. Many thanks to the House of Music of Hungary and the audience of Budapest for opening their hearts to the Joropo de Cimarrón!

Thank you very much for the interview, and we are all wishing Cimarrón continued success.

After the concert, the musicians of Cimarrón were celebrated by Hungarian and Colombian fans. The Ambassador of Colombia to Hungary H.E. Ignacio Enrique Ruiz Perea and his family, along with the Colombian Embassy staff, also attended the concert and congratulated Cimarrón for their impressive performances.

Photo gallery of the concert in Budapest:

Photos: Courtesy by Cimarrón and DPA