Edited by Anna Popper

For 2,000 years, the story of Jesus’ birth in Bethlehem – and Christmas itself – has shaped art, thought, belief, and human creativity in a way unlike anything else. This is especially true in Italy, where the Nativity is felt not only in churches and homes, but also in the country’s culture, aesthetics, and living traditions.

During the 2025 Christmas season, I have found myself thinking back to one of my many journeys to Italy – a country that has inspired me throughout my life and shaped the way I see the world. Years ago in Rome, standing before the grand Nativity display in St. Peter’s Square, I encountered a uniquely heartwarming Italian tradition: the Presepe (or presepio) – the Manger, or Nativity scene – depicting the Holy Family with the newborn Jesus in Bethlehem, built with human-scale figures. Still vibrant today, it captures the Italian Christmas spirit: warmth, devotion, and a refined sense of decoration that turns faith into art.

The Art of the Manger

During Advent and the Christmas season, thousands of presepi appear across Italy, inspired by the Neapolitan tradition, rich in local touches and peopled with figures drawn from everyday life, regional history, and beloved local saints and heroes: in churches, city squares, front gardens, and private homes. Often, an entire “Bethlehem” is recreated around the stable: marketplaces with stalls and craft workshops, animals, houses, and scenes of daily life. These details frequently reflect local customs and the maker’s own world rather than historical first-century Judea – an imaginative blend that is part of the presepe’s enduring charm. Traditionally, although the scene is set up before Christmas, the figurine of the infant Jesus is placed in the manger only on Christmas Day, 25 December.

The tradition is credited to Saint Francis of Assisi, who created the first Nativity scene in 1223 in the small town of Greccio in central Italy. Following his emotional visit to the Holy Land, he created a visual representation of the event. St. Francis’ presepe was a living one: real people and animals embodied the biblical figures – Mary, Joseph, the shepherds, the Magi, and the angels – often played by local villagers in a recreated Bethlehem.

The oldest known Nativity scene is a work of art: a white-marble masterpiece carved in 1290 by Arnolfo di Cambio, the renowned Gothic sculptor and architect who worked in Florence and Rome. This extraordinary Nativity can be seen in Rome at the Museum of the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore.

The presepe as a highly developed art form flourished particularly from the early 18th century onward, reaching an artistic peak in Naples (Napoli). There, the making of Nativity scenes became a craft mastered over centuries – rich in talent, theatrical detail, and imagination. From November through the Christmas period, the shops along Via San Gregorio Armeno – famous for artisans of the Neapolitan tradition – are often crowded with locals and visitors.

Even today, living Nativity scenes are organized during the Christmas season in many Italian towns and cities. Volunteer groups stage elaborated re-enactments in squares, streets and indoor venues. These performances involve hundreds of participants in a shared celebration.

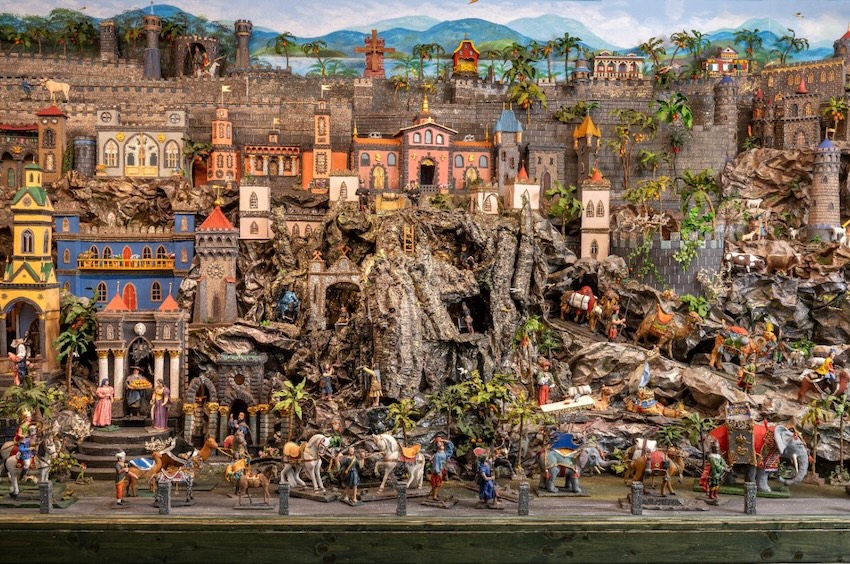

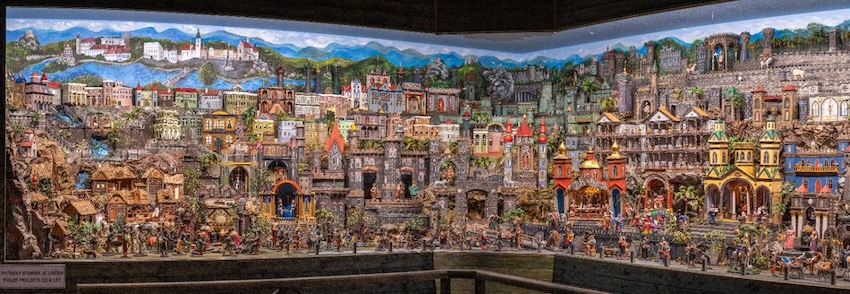

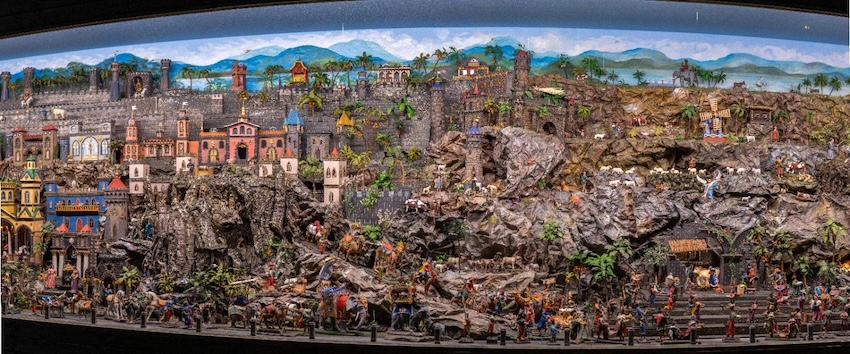

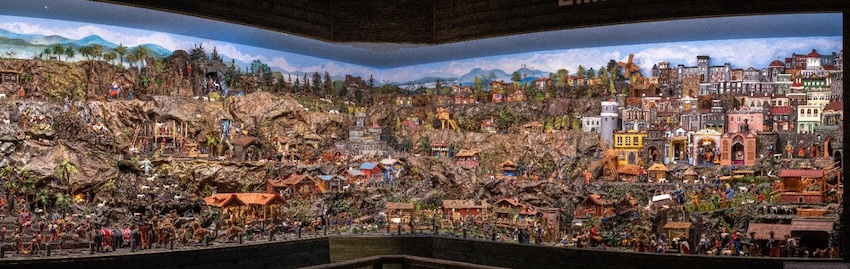

Naples’ Museo Nazionale di San Martino houses one of Italy’s most important Nativity collections, and its centrepiece is the celebrated “Presepe Cuciniello”, named after Michele Cuciniello (1822–1897), an architect, scholar, and passionate collector who assembled and expanded an outstanding ensemble of 18th-century Neapolitan figures and, in 1879, donated it to the Certosa di San Martino. The scene, with 162 human figures, 80 animals, and 450 miniature objects, unfolds like a miniature theatre in which the Nativity is set within a bustling, vividly human world of markets, musicians, artisans, animals, and everyday characters – capturing the essence of the Neapolitan tradition. There is something both playful and solemn about the Neapolitan tradition – in a word, something entirely human.

Christmas Tree and Presepe at Saint Peter’s Square Rome

The Vatican’s Christmas tree is a 27-metre-high spruce tree erected in Saint Peter’s Square, coming from the autonomous province of Bolzano, in Trentino–Alto Adige. It is offered in collaboration between the municipalities of Lagundo and Ultimo, located in the western part of South Tyrol.

This year’s Vatican Nativity scene came from the Diocese of Nocera Inferiore–Sarno, in the region around Naples and Salerno (Campania), and unmistakably Neapolitan in its classical tradition. The Nativity scene displayed in Saint Peter’s Square comes from the province of Salerno, in Campania, from the diocese of Nocera Inferiore–Sarno. It is a representation that incorporates typical elements of the Nocera area. In the centre there is the main scene with Jesus, Mary and Joseph, with the ox and the donkey, the Three Magi worshipping the Child and a shepherdess offering the riches of the diocese: vegetables, artichokes, walnuts, Nocera spring onions, San Marzano tomatoes. Two bagpipers accompany the scene with music. There are also other characters, such as a shepherd with the features of the Servant of God Alfonso Russo, symbolising the value of suffering and voluntary work. The entire scene is dominated by a large, bright comet with a tail in the shape of an anchor.

The “100 Nativity Scenes in the Vatican” – 2025

The 8th annual edition of the International Exhibition “100 Nativity Scenes in the Vatican” is back as part of the “Jubilee is Culture” season. The exhibition brings together works by artists from all over the world who have shown their creativity in producing Nativity scenes.

The exhibition was opened on 8 December 2025, under the left-hand Colonnade of Bernini, in St. Peter’s Square in Rome. This unique setting houses the numerous nativity scenes, which are real works of art, and invites visitors to admire the traditional scene of the Nativity of Jesus and to give thanks for the grace of the Holy Year, ending this year.

This year, 132 nativity scenes are on display from 23 countries, including Italy, France, Croatia, Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Romania, and Switzerland. Countries from other continents such as the United States, Peru, Eritrea, Korea, Venezuela, Taiwan, Brazil, Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Paraguay, and India are also participating or represented by their respective embassies to the Holy See. The nativity scenes reflect the inspiration and imagination of the artists who created them using a wide variety of materials. The exhibition is open to 8 January 2026.

In Italy, one of the best-known international Christmas events dedicated to the Nativity is the International Exhibition of Nativity Scenes (Presepi dal Mondo) in Verona, held at Palazzo della Gran Guardia each December/January for 36 years. The exhibition showcases hundreds of artistic and folk Nativity scenes from around the world.

It is also worth noting how strongly the Italian presepe influenced Nativity traditions abroad, spreading to countries such as Austria, Germany, Czechia (historical Bohemia), France (Provence), Poland, the Vatican, and even across the Atlantic.

A remarkable example outside Italy is the monumental crèche created by the Czech stocking weaver Tomáš Krýza (1838–1918) from Jindřichův Hradec in South Bohemia, Czech Republic. He worked on it for over 60 years. Covering roughly 60 m² (17 meters long and 2 meters high), it contains 1,389 figures of humans and animals, 133 of them movable. Built from wood, flour, sawdust, gypsum, and fish glue, its mechanisms were originally powered by hand and later driven by a single electric motor. Since 1998, the Krýza crèche has been listed in the Guinness Book of World Records. Today it is exhibited at the Museum of Jindřichův Hradec (www.mjh.cz). The region itself has a long Nativity tradition, with the first written record dating to 1579.

Italy is often described as the birthplace of the Christmas carol tradition as well. According to popular accounts, Saint Francis of Assisi encouraged carolling around the time of the Greccio Nativity in 1223 – introducing simple songs that people could sing anywhere, as an expression of joy at the birth of Jesus Christ, distinct from more formal church hymns.

Sources and Photos: Vatican News www.vaticannews.va, www.100presepi.va

Museum of the Basilica Santa Maria Maggiore, The Museo Nazionale di San Martino,